As the violence in the town of Ferguson, MO (about 19 miles north of St. Louis) begins for a second time, I'd just thought I ought to take a couple minutes to provide what I hope to be helpful feedback on the situation. I don't intend to make any comment on the case of Michael Brown itself, however; instead, I'd like to address the present circumstances.

The U.S. Constitution guarantees all U.S. citizens certain rights on the law. These rights are meant to safeguard our basic needs as human beings and prevent government or other entities from oppressing our freedoms. However, as with many of our rights, we all too frequently ask where the most extreme boundaries of our rights end and far too infrequently ask whether the current time, place, and circumstance is appropriate for us to exercise our rights. Too much time spent asking questions like if the exercise of a Black Mass is within our right to free speech, and not enough time realizing why refraining from reciting our political beliefs in a public library is actually a good idea.

Among other important points, the First Amendment grants citizens the right to assemble peacefully. Naturally, as U.S. citizens, the people of Ferguson and beyond have taken up their rights to freedom of speech and assembly by taking to the streets of their town in protest, most of them peacefully. However, some of the crowd has proven to be violent and in the days after the initial shooting in August, many of these acts of looting and violence were committed by people who weren't even from Ferguson. These people do not care for Michael Brown, nor do they care for the town of Ferguson, as they look to profit from her destruction. Though I have little doubt the case is the same today, time will tell if those responsible for the recent destruction are from out of town.

For the Ferguson police and others responsible for keeping law and order in the area, I have no doubt that each officer gearing up for each night prepares himself mentally for the violence that he may encounter. Knowing that violence in these volatile situations is imminent, they take no chances when it comes to weaponry, body armor, and other safeguards. Ferguson has become a war zone, and those officers have the difficult task of maintaining the rule of law, for everyone's sake. But for now, I'm sure each one of them just wants to make it through the night and back to their families.

This time, this place, and these circumstances makes the town of Ferguson the inappropriate site to exercise our freedom of assembly. And it is the duty of every single peaceful Ferguson citizen to realize that and stay off the streets and out of the way of police. It doesn't matter how peaceful you've made your protest. If it's in the streets of Ferguson, you're only getting in the way of those tasked to uphold law and order and as a result, become complicit with the destruction, burning, and looting of local businesses and the welfare of your next-door neighbors. The dinner bell has been rung, and the vultures who would use your peaceful protest as an excuse to create mayhem and carnage will bring destitution upon your town.

Does this mean that citizens upset by the decision should just accept it and move on with their lives? No. But there are certainly other, more creative and sensible ways to peacefully protest than to hinder the police from effectively saving your town.

Tuesday, November 25, 2014

Sunday, October 12, 2014

We Really ARE Conscious!

To date,

I haven't written anything reactionary; however, it's also important to accept

that truth does not exist in a vacuum, hence the reason for this post. The

subject of debate is the opinion article in the New York Times entitled, "Are We

Really Conscious?" written

by Princeton-educated Michael Graziano PhD (in neuroscience) and currently an

associate professor at his alma mater. His psychology work is just one part of

his CV, which also includes 3 literary novels, children's books, and symphonic

works.

While I

haven't delved into these works to discover their merit, I think his most

recent work in the New York Times is ‘more of the same’ when it comes to the

sophistry of the modern academic sciences. While I certainly cannot hope to

refute his claims on grounds of neuroscience (his expertise), I must

demonstrate a number of fallacious

assumptions made on logical and philosophical grounds (my expertise).

To

summarize the opinion, Dr. Graziano is presenting his "attention

schema" theory of human consciousness. The theory begins by defining two

terms:

attention: a

physical phenomenon

awareness: our

brain’s approximate, slightly incorrect model of our attention

The

example he uses of the theory in practice is our perception of light. The

wavelength of the light is the true attention of the light, or in his words,

"a real, mechanistic phenomenon that can be programmed into a computer

chip." The occurrence of the light, therefore, is something entirely

quantitative, whereas our brain creates the "cartoonish reconstruction of

attention" that we know as 'color', which is our awareness. While the

quality of color has been assumed to be only a construct of the human mind

since the Enlightenment philosophers, science has proven that white light is

actually comprised of light with many different wavelengths, meaning that light

is comprised of many (in fact, all) colors. Therefore, the attention is that

data of many wavelengths/colors and the awareness is what we'd mistakenly call

"white light".

What does

this have to do with consciousness? Dr. Graziano equates our brains as

informational storehouses, like computers, whose sole purpose is to retain and

process information. The subject of consciousness arises when faced with the

difficult question of why the brain would inefficiently waste energy on

defining itself as something separate from its surroundings and be aware that

its experiences are subjective. He then presents his attention schema theory to

explain consciousness as a rude approximation of the information it processes,

similar to how white light is only an erroneous estimation of all colors

together.

However,

a critical look at Dr. Graziano’s distrust for our intellect reveals a

misplaced trust in the inventions created by our very own intellect. (I will,

for the purposes of this post, roughly equate Dr. Graziano’s term ‘awareness’

to the term, ‘intellect’, because it is our intellect with which we interpret

the information received from our senses) Our intellect was the creational

source of the computer, the camera, and the spectrometer; these human

inventions are as limited in their design as their poor human inventors.

Returning to Dr. Graziano's example of the computer chip, it is our intellects that program that computer chip to

recognize wavelengths. They do not function any different than how we designed

them to function, and if they see phenomena that we don’t, it is only because

we possessed the intellect to speculate that phenomena’s existence.

Even the

scientific terminology used by Dr. Graziano is a creation of the human

intellect of which we should be skeptical. Pre-modern science, we created the

vocabulary of ‘green’ and ‘white’ light because those are the terms we used to

describe the phenomenon of different kinds of light. With modern science, we

created the vocabulary of ‘495 nm < λ < 570 nm’ and ‘390 < Σλ < 700

nm’ to describe the exact same phenomenon. Both vocabularies are constructs of

our own intellects, intended to conform to an external reality and

differentiated only by their specificity. And still, our scientific expression

is limited by the understanding of our intellect. Just as Newton’s theory of

gravitation was not the final word, so too many of our other constructs of intellect

(i.e. the color of light, the wavelength of light, etc.) will be overturned

again and again as our intellect struggles to grasp the natural cosmos. So in this sense, we cannot escape from our own intellect!

These were the words

chosen by Dr. Graziano, but for the sake of argument, we can assume that Dr.

Graziano oversimplified his definition of 'attention' for the benefit of the

reader. An alternate understanding may be the true nature of the phenomenon itself

that is unknown to us at the time. For example, before Newton, scientists did

not yet realize that white light was comprised of all colors of the visible

spectrum and they their combined wavelength creates white light. Now, let's

suppose that this is the correct understanding of light as it really is

(meaning, that this is what white light essentially is, and no further

modification to our electromagnetic theory will be ever necessary). This makes

the definition of attention to be independent of anything man-made.

But even with this

understanding, Dr. Graziano still commits two debilitating errors: one logical

and the other epistemological. The logical error, being the more rudimentary,

we will examine first. Dr. Graziano uses man’s mistaken postulate that white light

is purely a single color to cast doubt over the existence of man’s

consciousness. He uses the erroneous attribution of quality of one thing to

demonstrate the erroneous attribution of existence to another. As with the

popular saying concerning "apples and oranges", this is not a

logically coherent analogy. Basic logic instructs that attributes are predicates

of the subject. For example, the statement, “White light is not a single color” has ‘white

light’ as the subject, and “not a single color” as a negative predicate attributed

to that subject. However, it would be absurd to say, “White light is NOT” or

rather, “White light does not exist” because obviously the phenomena of unified

light does exist or else we would not be theorizing about it. The equivalent would be

to first claim, “Gravity is not a kinematic force,” (which is predicted by

theory and has been supported by repeated experimentation) then to claim, “Gravity does not exist,”

after which, to test this claim, one must simply jump off a 10-story building

to realize his error. Dr. Graziano assumes that existence is an attribute that

we associate with a thing, like the green color of grass (or photosynthesizing chlorophyll, if we want to be scientifically accurate). He

then carries his error with him in the analogy to the existence of one’s consciousness,

mistaking attribute for existence and proposing a comparison that fails under

the scrutiny of logic.

At a deeper

philosophical level, Dr. Graziano also mistakes the object apprehended by the

intellect to be scientific fact. Rather, the immediate object of our intellect

is ‘being’ per se and not the quality, quantity, or any attributes whatsoever. The

intellect, guided by the light of Reason, apprehends the existence of phenomena

with certainty. While it is historically true that our intellect mistakenly

believed that white light was unique from green light (and not composed of all

colors), our intellect remains certain of the existence of the phenomenon that we

describe as ‘white light’.

Therefore,

acceptance of Dr. Graziano’s theory serves only to submerge the reader beneath

the quicksand of his initial premise: skepticism. Doubt in our own intellect

undercuts the vast expanse of theories and hypotheses that comprise the natural

sciences, not to mention our very rational existence. Any honest intellect that

chooses to accept this initial premise must commit intellectual suicide, and

make vegetables out of their own mind.

To the

contrary, a disciplined intellect is the cause of truth in the mind, though

truth is by no means easy to obtain. It is with great difficulty that we arrive

at truth. Therefore, while misuse of one’s intellect results in error, well-reasoned

and careful application of the intellect yields the fruit of certain truths.

Monday, February 24, 2014

Humble Servitude and the Good Master

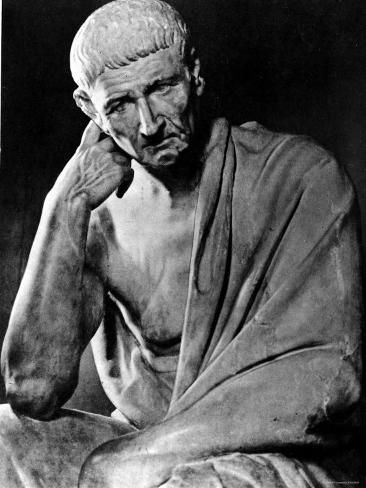

In writing my previous post on Aristotle in the "Highest Human Science Series", I had the opportunity to review one of his more controversial philosophical views. I say "controversial", but only because our too-often arrogant modern perspective shuts us off from learning anything about the world unless it comes from a contemporary and up-to-date 'world-view'. Our tendency to ignore great thinkers and men of virtue from history just because they didn't have the Internet is a handicap that makes any attempt at intellectual honesty evaporate instantly. I think that's a topic for another time.

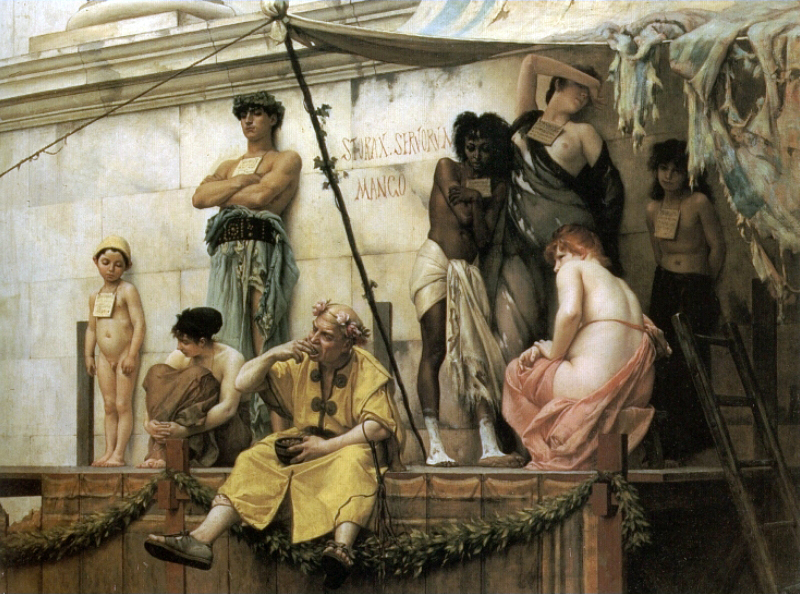

The Aristotelian doctrine that I am referring to is his commentary on the composition of the household. In Chapter 3 of Politics I, the Philosopher starts from the basic communities, these being man and woman or a master and a slave, and works his way up to the city-state. However, in Chapter 5, he makes the very startling claim, and I quote directly from C.D.C. Reeve's translation:

"... There are some people, some of whom are naturally free, others naturally slaves, for whom slavery is both just and beneficial." (Pol I.5 1225a 2-4)"

To the careless reader, this might be enough to stop reading and move on to a task which requires significantly less intellectual digestion. However, can this really be true? I do not hold individuals' opinions in high honor unless I have heard all of it and find all of it honorable. This pricks that nagging, hopelessly modern part of my conscience that is the mark of everyone born in this age of history. But it's so aggressively bold that given how high I have admired Aristotle's intellect up to this point, I am willing to give him a fair shot.

Aristotle's understanding of "slave" is not at all the same as that which we typically hold when reflecting on our nation's history. True, he is most likely referring to slaves taken in the conquest of one nation over another, but the imagery of Uncle Tom's Cabin is a modern intellectual prejudice exclusive to human thought in the last few centuries.

Aristotle uses the term "natural slaves" to denote that these men (or women) are made slaves by nature. So in this sense, he is not strictly referring to those slaves won as spoils of military conquest. Instead, these human beings had it in their nature to be slaves from birth. As a biologist by study, Aristotle gravitates towards assigning the distinction of "by nature" to his observances. However, he does have proof to back this up. He asserts that, "Nature tends... to make the bodies of slaves and free people different," specifically, a slaves body is physically superior to that of a free person's. (Pol I.6 1254b 26) Harkening back to his argument about function, it is plain to see that a strong body is best suited for tasks that are physically strenuous.

Also, though I do not fully agree with the sweeping generalization of this next statement, he also points out that the natural slave "shares in reason to the extent of understanding it, but not have it himself." (Pol I.6 1254b 22-23) This statement makes it clear (and if it doesn't, he makes it more obvious later in the work) that according to Aristotle, natural slaves do not possess reason at all. However, to avoid getting into an entirely tangential argument on what Aristotle is actually saying, I think we can sufficiently agree that the people that tend to end up at the bottom of the pile are those less capable of intellectually robust activity than those above them. So I think it is fair to say that though Aristotle's statement above might not ring entirely true; there's enough to it that I can believe it to an extent.

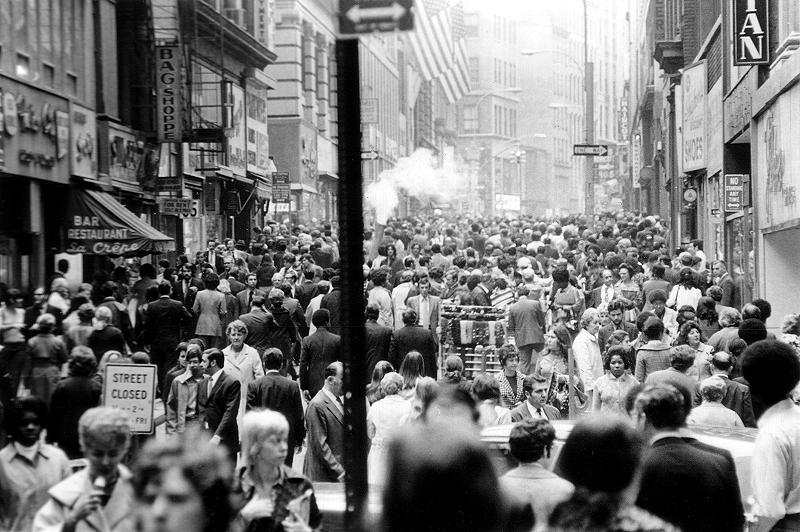

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own.

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own.

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own.

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own. At this point, my conclusion is that Aristotle was definitely on to something when he defines the natural slave. Though I might not agree with every characteristic that he associates with them, I do accept that there are persons capable of understanding human reason, though incapable of vigorously applying it themselves.

But to return to the initial claim, Aristotle's view that slavery could ever be both "just and beneficial" is still very difficult to swallow, despite the natural slave only being fit for physical labor (as shown above). Though without any guidance to his labors, he would be useless and unproductive. For it to be just, it would have to be in accordance with the virtue of justice and fittingness; and for it to be beneficial, it would need to be in the individual's best interest to be ruled by another man.

If a natural slave were to be ruled by another man, then who more beneficial to his interests than the virtuous, or eudaimon, man? Given the master's virtue, he would be of a superlative intellect, as contemplative wisdom, along with action-based practical wisdom, are the crowning achievement of the virtuous man and the most visible marks of his intellectual prowess.

Furthermore, without the capacity for agile rational activity, natural slaves are incapable of full human virtue, according to Aristotle; however, in the company of a virtuous master, the natural slave could share in his master's intellectual wisdom and share in living a virtuous life. Aristotle is very scrupulous when it comes to assigning the term, "virtuous". Both excellent acts and thoughts are require for the virtuous man, and on those grounds, the natural slave is disqualified from the title unfortunately. While I agree with this on the grounds that to achieve the highest status of any human being, you must perform your function the best, I believe there is a similar value and virtue associated with knowing your intellectual betters and modeling your conduct and contemplation after theirs.

And it is here that I think we have come across the most helpful and universally practical nugget in this lonely corner of Aristotle's political theory. Modern thinkers would never have discovered it because modern thinkers wouldn't have made it past the first paragraph. But we have. To some degree, we are all natural slaves; there is something deficient in our human understanding and it's something we can always work on. We need to make our understandings subservient to virtuous men; we must sit at the feet of the intellectual masters and allow ourselves to be guided by their practical and contemplative wisdom. In modern terms, it is comparable to discovering our role models and fashioning our thoughts and behavior from theirs.

To conclude, when considering Aristotle's political and ethical theory in its entirety, I believe he presents the most mature and responsible blueprint for a society that permits servitude. His biological (natural) perspective may overstep its bounds in some respects to a comprehensive understanding of the nature of all human beings, but in the end, he holds the masters of other men to high standards of conduct and responsibility in governing those under their charge. And in applying Aristotle's theory of natural slavery broadly with a little humility, we discover that we could all allow ourselves to cease our intellectual rebellions and naturally "enslave" our minds and hearts to men and women of high and admirable virtue.

If a natural slave were to be ruled by another man, then who more beneficial to his interests than the virtuous, or eudaimon, man? Given the master's virtue, he would be of a superlative intellect, as contemplative wisdom, along with action-based practical wisdom, are the crowning achievement of the virtuous man and the most visible marks of his intellectual prowess.

Furthermore, without the capacity for agile rational activity, natural slaves are incapable of full human virtue, according to Aristotle; however, in the company of a virtuous master, the natural slave could share in his master's intellectual wisdom and share in living a virtuous life. Aristotle is very scrupulous when it comes to assigning the term, "virtuous". Both excellent acts and thoughts are require for the virtuous man, and on those grounds, the natural slave is disqualified from the title unfortunately. While I agree with this on the grounds that to achieve the highest status of any human being, you must perform your function the best, I believe there is a similar value and virtue associated with knowing your intellectual betters and modeling your conduct and contemplation after theirs.

And it is here that I think we have come across the most helpful and universally practical nugget in this lonely corner of Aristotle's political theory. Modern thinkers would never have discovered it because modern thinkers wouldn't have made it past the first paragraph. But we have. To some degree, we are all natural slaves; there is something deficient in our human understanding and it's something we can always work on. We need to make our understandings subservient to virtuous men; we must sit at the feet of the intellectual masters and allow ourselves to be guided by their practical and contemplative wisdom. In modern terms, it is comparable to discovering our role models and fashioning our thoughts and behavior from theirs.

To conclude, when considering Aristotle's political and ethical theory in its entirety, I believe he presents the most mature and responsible blueprint for a society that permits servitude. His biological (natural) perspective may overstep its bounds in some respects to a comprehensive understanding of the nature of all human beings, but in the end, he holds the masters of other men to high standards of conduct and responsibility in governing those under their charge. And in applying Aristotle's theory of natural slavery broadly with a little humility, we discover that we could all allow ourselves to cease our intellectual rebellions and naturally "enslave" our minds and hearts to men and women of high and admirable virtue.

Tuesday, December 10, 2013

A Small Coffee Shop...

The King’s Coffee is more than just a caffeinated beverage. It’s a culture. In a world where Red Bull and Monster energy drinks get people their caffeine drug fix or where Starbucks serves up sugar comas by the environmentally-friendly disposable cup, coffee seems to have lost the fine traditions and culture that have surrounded it in its long history. But not here.

Here, there is inspiration. The rustic and uniquely librarian feel to the shop encourages the next great idea, whether you’re a student cramming for a test, an entrepreneur talking over the next big thing with your business partners, or even just a part-time philosopher like me. Building on centuries of coffee tradition, we believe that the coffee house is a source of intellectual discussion, break-through ideas, and the search for truth. From handcrafted wooden tables to our old-fashioned library, the contemplative atmosphere of The King’s Coffee encourages adventure into uncharted ideas. Literary classics can be removed from the library shelves and perused while you sip your coffee or even purchased before you go.

If you will be staying with us as you enjoy your coffee, you can select your favorite, unique coffee mug from our Wall of Mugs. No two mugs are exactly the same and each one has been handcrafted to create a unique experience with each visit to our shop. When you’re finished with the mug, you may either return it or purchase it at the register. If you choose to purchase, know that it is the only one exactly like it and no duplicate will ever be crafted. The uniqueness of your experience at The King’s Coffee is ultimately the measure of our success to create an inspirational and intellectual prolific atmosphere. Though we do also offer to-go cups and lids, we encourage our patrons to enjoy the quiet and thought-provoking atmosphere of the shop.

As much as coffee is a stimulant of the intellectual exercises, we believe that it unlocks the artist in all of us. The walls of the shop are adorned with beautiful artistic originals from local artists to create a perpetual art show for our patrons. Art may also be purchased off the wall and new works will be rotated in as they are received for display. The finer arts will permeate the audible surroundings as well, exhibiting only the finest classical music selections.

Finally, the coffee itself will reflect all of the values inherent to the mission of The King’s Coffee. All of our beans are roasted to perfection on site, treated with the highest care to ensure freshness and quality. Coffee is freshly ground to ensure that your cup of coffee is handed to you in prime flavor. Temperatures of brewed coffee are monitored to prevent coffee from burning and becoming bitter, and only the purest quality spring water is used.

So step into The King’s Coffee and revitalize your intellectual inspiration with a mug or two of our fine coffee!

Saturday, November 2, 2013

The Highest Human Science: VI. Aristotle

This is a post from the series, "The Highest Human Science". Click here for a complete list of all posts in the series.

It has been quite some time since I last posted to this series, but I have returned to it, drawn by the most important (and my favorite) chapter of it all. Thus far, we have seen Man's attempts at making sense of the confounding world in which he lives. These studies led him to ask the questions around the material and immaterial compositions of things, the purpose of reason, and the search for truth.

It has been quite some time since I last posted to this series, but I have returned to it, drawn by the most important (and my favorite) chapter of it all. Thus far, we have seen Man's attempts at making sense of the confounding world in which he lives. These studies led him to ask the questions around the material and immaterial compositions of things, the purpose of reason, and the search for truth.

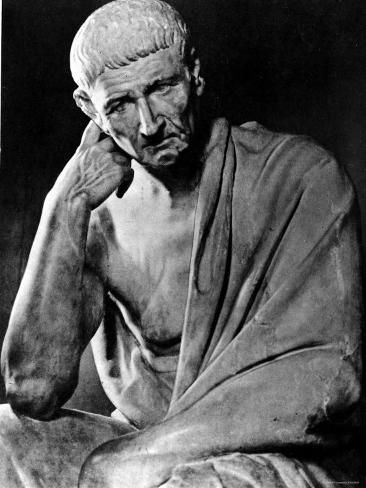

Poised and prepared to give the course of human wisdom one last mighty turn, Aristotle, a resident alien of Athens and a student of Plato, accepted

the challenge of traversing the intellectual mountain that even his

masters before him were unable to navigate, error-free. He took all of

the good conclusions and thoughts from the teaching of Socrates, Plato, and the other noteworthy philosophers and purified them of their errors, solidifying a reality for the

human intellect to comprehend. With each piece in it's proper place, he would create the true philosophy, one which if all basic principles were properly understood, would be the most excellent starting point for mankind's intellect.

A biologist by study, Aristotle's teachings and writings appeal to the practical mind and those for whom primary understand comes from their senses and experience. He did not abstract often, and applied his reason to his experiences and using fundamental philosophical principles, explained the natural world around him. In that sense, his philosophy remains perfectly balanced between the appeal to the sense and the consideration of immaterial, unchanging philosophical principles.

It is very difficult to know where to start with Aristotle, since his worldview is so tightly knit and coherent that various branches of the main shoot will often return and be interwoven with other topics of his study.

Probably the best place to begin would be the fundamental basis on which his principles differed from Plato, his instructor. Plato's theory of substance and form had them separate: matter existed here on earth, imperfect and perceivable to the senses, while the form of a thing resided in the heavens and is the goal of our contemplation. Aristotle's view, on the contrary, places the form and matter of a thing in same entity. This dispelled the thought that the world around us was only a deception of reality and instead, established that the world around us was indeed reality.

To aid in our understanding of this, we will consider the example from the previous post of a glass of wine. It's true that in attempting to determine the essence of wine, we will arrive at an understanding of the form. But instead of each glass of wine suggesting to our intellects that there is some perfectly Wine form in heaven (according to Plato), our reason perceives a "trend" in individual physical manifestations of one idea. Therefore, a glass of wine doesn't help us to know what the perfect heavenly form is (suggested by Plato), it helps us to determine what the glass of wine itself actually is. The "matter" of wine (sugars, proteins, alcohol, etc.) all could take any other form, but the fact that the matter takes the "form" of wine is something present abstractly, though tangibly in the organization of these material ingredients to present to our senses "wine", in both form and matter (as opposed to "bread" or "wood").

In categorizing the substance and accident of a thing, Aristotle identified the two of his four "causes": the formal cause and the material cause. All together, the four causes answer the questions of "why" a thing is the way it is. The third cause is the efficient cause, which is the motivator of change within the thing. For example, the combination of nutrition in a child and the natural tendencies of his body is the efficient cause of his growth. The fourth and final cause is just that: the final cause. It is that which is the end or natural destination of the thing; it is that for the sake of which the being exists.

In categorizing the substance and accident of a thing, Aristotle identified the two of his four "causes": the formal cause and the material cause. All together, the four causes answer the questions of "why" a thing is the way it is. The third cause is the efficient cause, which is the motivator of change within the thing. For example, the combination of nutrition in a child and the natural tendencies of his body is the efficient cause of his growth. The fourth and final cause is just that: the final cause. It is that which is the end or natural destination of the thing; it is that for the sake of which the being exists.

In categorizing the substance and accident of a thing, Aristotle identified the two of his four "causes": the formal cause and the material cause. All together, the four causes answer the questions of "why" a thing is the way it is. The third cause is the efficient cause, which is the motivator of change within the thing. For example, the combination of nutrition in a child and the natural tendencies of his body is the efficient cause of his growth. The fourth and final cause is just that: the final cause. It is that which is the end or natural destination of the thing; it is that for the sake of which the being exists.

In categorizing the substance and accident of a thing, Aristotle identified the two of his four "causes": the formal cause and the material cause. All together, the four causes answer the questions of "why" a thing is the way it is. The third cause is the efficient cause, which is the motivator of change within the thing. For example, the combination of nutrition in a child and the natural tendencies of his body is the efficient cause of his growth. The fourth and final cause is just that: the final cause. It is that which is the end or natural destination of the thing; it is that for the sake of which the being exists.

With this notion, Aristotle's metaphysics laid the groundwork and justification for his ethics; since the ideas we have in our heads come from our senses, it is our job to form the correct ideas from what our senses present to us. Although our understanding may err, our senses, if they be not defective, never lie. Having established that the physical world around us is a reliable source of information, Aristotle proceeds to answer the question of what man "must do" by demonstrating the "good" of man. It is towards the pursuit of this good that all of man's actions should be directed, and this good is virtue. I won't go into too much detail on this here, but you can find a more detailed study of this on one of my previous posts, "The Human Good".

In determining the good of one man, Aristotle deals with the good of all men in his Politics. His method stems from beginning with those foundations of politics that do not stem from "deliberate choice", namely that between husband and wife or master and slave. Neither can subsist without the other and so this is a necessary community. From this, Aristotle expands to a household, which includes children and servants, then to a series of households to form a village or colony.

The point of self-sufficiency is where Aristotle draws the line of what was known in ancient Greece as the polis or "city-state". The city-state comes into existence for the sake of existence and is the necessary end of the primal relationships between man and woman, master and slave. In this way, Aristotle claims that the polis is a natural organization, which makes man, by nature, a political animal.

Though I have only barely scratched the surface of the breadth of Aristotle's intellectual genius, I hope the reader has retained at least a preliminary impression of Aristotle's contribution to the study of human reason and wisdom. It seemed difficult to even hope that the human race would be so graced with the blessing of just one such intellectually masterful man; however, with the teachings of Jesus Christ (approximately 300 years after Aristotle) and the addition of this divine perspective, the study of human reason would need some finishing touches before all was said and done...

The point of self-sufficiency is where Aristotle draws the line of what was known in ancient Greece as the polis or "city-state". The city-state comes into existence for the sake of existence and is the necessary end of the primal relationships between man and woman, master and slave. In this way, Aristotle claims that the polis is a natural organization, which makes man, by nature, a political animal.

Though I have only barely scratched the surface of the breadth of Aristotle's intellectual genius, I hope the reader has retained at least a preliminary impression of Aristotle's contribution to the study of human reason and wisdom. It seemed difficult to even hope that the human race would be so graced with the blessing of just one such intellectually masterful man; however, with the teachings of Jesus Christ (approximately 300 years after Aristotle) and the addition of this divine perspective, the study of human reason would need some finishing touches before all was said and done...

Monday, October 28, 2013

The Most Rare Human Virtue

As with many of the inspirations I have for posting something to this blog, I could most often cite TheArtofManliness.com as a common source. The blog/website is a fantastic source of information and helpful encouragement for those who wish to see more in their fellow man. Recently, Mr. McKay "retweeted" an article that appeared in a 1902 issue of Cosmopolitan Magazine (of all places). The post can be found here and the material is from the article entitled "What Men Like in Men", written by Rafford Pike. I started reading down the page and I came to this paragraph, reproduced here for the reader's convenience:

"... The average man will name a number of qualities which he thinks he likes, rather than those which in his heart of hearts he actually does like.

In the case of one who tries to enumerate the characteristics which he admires in other men, this sort of answer is not insincere. Although it is defective, and essentially untrue, the man himself is quite unconscious of the fact. The inaccuracy of his answers really comes from his inability to analyze his own preferences. The typical man is curiously deficient in a capacity for self-analysis. He seldom devotes any serious thought to the origin of his opinions, the determining factor in his judgments, the ultimate source of his desires, or the hidden mainsprings of his motives. In all that relates to the external and material world he observes shrewdly, reasons logically, and acts effectively; but question him as to the phenomena of the inner world – the world of his own Ego – and he is dazed and helpless. This he never bothers his head about, and when you interrogate him closely and do not let him put you off with easy generalities, he will become confused and at last contemptuous, if not actually angry. He will begin so suspect that you are just a little “queer”; and if he knows you well enough to be quite frank with you, he will stigmatize your psychological inquiries as “rot.”…"

At this point, I looked ahead to see how many more paragraphs were left in the article and though I returned to read the rest of the article later (this was only the second paragraph, mind you), I had decided that the mission of the article had already been fulfilled: it had just stated what I admire in other men (and other women, for that matter).

Human virtues, like anything else of value, are prized for their rarity among men, and just as a flawless diamond takes much perseverance and hard work to obtain due to its rarity, virtue also is rare because of the demands it makes on the man who seeks it. If human virtues were as abundant as blades of grass in a field or grains of sand in a desert, we would assign them the same value as these. However, virtue is not that easily found or obtained, so it is natural that we value it in other men.

The most rare of all human virtues is self-awareness, or maybe more accurately, self-comprehension. It is rare because those who seek it must do battle with the most common and deadly of the human vices: pride. Self-comprehension permits every agent in an environment to be judged in the context of that environment, including the individual himself. This man understands that when judging a situation or situation of persons, he is never exempt from being included in those circumstances which he scrutinizes. Regardless of the subject matter, he always makes some alteration to that environment and thus must be included in its judgement.

In this manner, self-comprehension enables the individual to perceive himself in the context of his surroundings, almost as a completely alter-ego. The self-comprehensive man's gaze reaches farther from an independent perspective than any person who fails to understand that his personality has effect on the circumstances. The mystery of why a friend is quick to temper with us is easily solved when we realize our own tendency to make inflammatory remarks.

The self-comprehensive man not only knows of his leanings and biases: he also knows why he has them. He keeps record of his influences, in a way, similar to a student citing his sources in a research paper. Every agreement he has to an idea is properly labelled and everything is organized. With this organizational system, it's not only important to know one's flaws or weaknesses, but it's knowing where those flaws and weaknesses originated from which set the self-comprehensive man apart from the rest as a gem of uncountable worth.

As the worth of virtue is in its practice, the worth of self-comprehension is most notably found in the practice of self-improvement. While self-awareness permits the man to admit to his failures and shortcomings, the self-comprehensive man does this and also understands why he fails in these ways. The answer to "why" is the answer to what strategies he must take to better himself, putting himself in a more advantageous situation than the sick man who knows that he's ill, but knows not why.

Saturday, July 6, 2013

The Highest Human Science: V. Plato

This is a post from the series, "The Highest Human Science". Click here for a complete list of all posts in the series.

Once more, we return to that most important study of philosophy, and this is indeed one of the more important chapters in our study of philosophical history. Up to this point, we've been discussing and looking into the various erroneous ways of thought from the ancient cultures and religions of the world, as well as the turn towards the reason properly, though misguidedly exercised in the early Greek thinkers. This all culminated in the great thoughts and teachings of Socrates, who would inspire one young student of his to change the scope of the entire study...

|

| Yes, a "Play-Doh" representation of Plato |

Plato (BC 427-347), student of the eminent Socrates and intellectual giant of his time was now given the torch of Philosophy: the standard of intellectual progress to further the understanding of mankind. Really, this was to be a vast task and not one lightly undertaken and for all this pressure riding on Plato... he didn't do half bad.

As a start, he believed in an ultimately perfect Being. He perceived that the things around him had perfection and imperfections mingled together, so it was not out of the realm of imagination to suppose that there was something after which all perfection was an imitation. This perfect being is the basis, the foundation and source for everything that we see.

Socrates' philosophy, as previously reviewed, is purposed towards determining the essences of things; Plato's thought, on the other hand had the goal of determining perfect ideas of things. For according to Plato, the apprehension of a particular thing's essence is well and good, i.e. what is the essence (or essential qualities) of this glass of Rex Goliath malbec wine that I'm drinking while writing this post, but what about wine as an idea? What is the essence of Wine, the idea? After all, these are universal to everyone. If I tell you I want wine, sure, you might bring me an expensive chardonnay or a cheap merlot, but the fact that with a word, "wine", you understood what I was essentially referring to, this indicated to Plato that there was an idea of Wine that we all shared in and could all comprehend. With this, the nature of wine could be contemplated and we could analyze what it essentially meant to be "wine-like".

|

| "Plato's Cave" by Jan Saenredam |

Though everything looks good, thus far, Plato's next thought led him off the beaten path and into his first error. He claimed that since these ideas are universal and with the ultimate perfections of these ideas, there must be an eternal archetype of "wine" that exists in the heavenly realm. It is this that we get a glimpse of when we think of the subject, though our perceptions may be imperfect, because the physical representations of this idea around us are imperfect (i.e., all the bottles of wine in the world just don't encompass the perfection of that single ultimate idea of wine). He called these perfect ideas the Forms, and it was the goal of our existence to obtain perfect apprehension of these holy ideas.

|

| A representation of Plato's Cave by Bryce Haymond |

This led Plato to claim that if perfection is to be found in the heavenly Forms, then the sensible world is to be regarded as a deceptive shadow of reality. This notion is the source of Allegory of Plato's cave. In essence, the citizens of the cave are chained the floor and are unable to look anywhere but the cave wall straight ahead, upon which is projected the shadows of characters and animations from a backlighting fire (similar to the notion of "shadow puppets") The sensible world, therefore, is only a crude representation of the truth, and a soul is meant to leave the cave and walk into the sunlight and see the world as it truly is.

So if these ideas, these perfectly divine Forms are what reality is all about, how do we have them in our heads? Certainly we didn't obtain them from our sensible experience of the world because the objects of this perception are imperfect. Plato claimed that we had previous knowledge of these ideas before our incarnation, and with our birth, our physical bodies and perceptions obscured these truths. He also subscribed to the mistaken belief (shared by the Brahmanist) of transmigration of the soul from one body to another after death.

Ok, so if we're honest, Plato is beginning to sound a bit hokey. Wine, shadow puppets, and transmigration? Sounds like a bad children's bedtime story. Though it would not be accurate to say that Plato completely dropped the ball with the intellectual inheritance that to which he was entrusted, he did screw up quite a bit and a more complete and accurate philosophy would be need to be built on Plato's good ideas before we could call it a day.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)