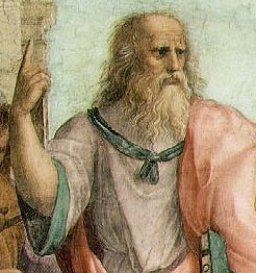

In writing my previous post on Aristotle in the "Highest Human Science Series", I had the opportunity to review one of his more controversial philosophical views. I say "controversial", but only because our too-often arrogant modern perspective shuts us off from learning anything about the world unless it comes from a contemporary and up-to-date 'world-view'. Our tendency to ignore great thinkers and men of virtue from history just because they didn't have the Internet is a handicap that makes any attempt at intellectual honesty evaporate instantly. I think that's a topic for another time.

The Aristotelian doctrine that I am referring to is his commentary on the composition of the household. In Chapter 3 of Politics I, the Philosopher starts from the basic communities, these being man and woman or a master and a slave, and works his way up to the city-state. However, in Chapter 5, he makes the very startling claim, and I quote directly from C.D.C. Reeve's translation:

"... There are some people, some of whom are naturally free, others naturally slaves, for whom slavery is both just and beneficial." (Pol I.5 1225a 2-4)"

To the careless reader, this might be enough to stop reading and move on to a task which requires significantly less intellectual digestion. However, can this really be true? I do not hold individuals' opinions in high honor unless I have heard all of it and find all of it honorable. This pricks that nagging, hopelessly modern part of my conscience that is the mark of everyone born in this age of history. But it's so aggressively bold that given how high I have admired Aristotle's intellect up to this point, I am willing to give him a fair shot.

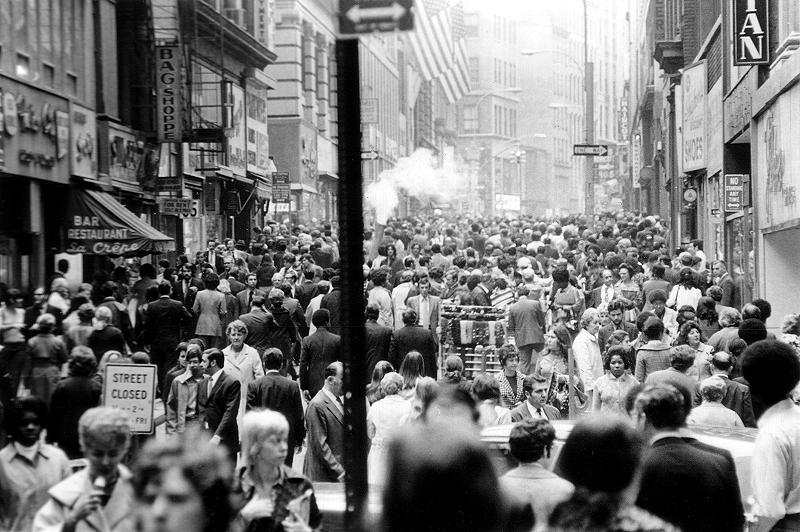

Aristotle's understanding of "slave" is not at all the same as that which we typically hold when reflecting on our nation's history. True, he is most likely referring to slaves taken in the conquest of one nation over another, but the imagery of Uncle Tom's Cabin is a modern intellectual prejudice exclusive to human thought in the last few centuries.

Aristotle uses the term "natural slaves" to denote that these men (or women) are made slaves by nature. So in this sense, he is not strictly referring to those slaves won as spoils of military conquest. Instead, these human beings had it in their nature to be slaves from birth. As a biologist by study, Aristotle gravitates towards assigning the distinction of "by nature" to his observances. However, he does have proof to back this up. He asserts that, "Nature tends... to make the bodies of slaves and free people different," specifically, a slaves body is physically superior to that of a free person's. (Pol I.6 1254b 26) Harkening back to his argument about function, it is plain to see that a strong body is best suited for tasks that are physically strenuous.

Also, though I do not fully agree with the sweeping generalization of this next statement, he also points out that the natural slave "shares in reason to the extent of understanding it, but not have it himself." (Pol I.6 1254b 22-23) This statement makes it clear (and if it doesn't, he makes it more obvious later in the work) that according to Aristotle, natural slaves do not possess reason at all. However, to avoid getting into an entirely tangential argument on what Aristotle is actually saying, I think we can sufficiently agree that the people that tend to end up at the bottom of the pile are those less capable of intellectually robust activity than those above them. So I think it is fair to say that though Aristotle's statement above might not ring entirely true; there's enough to it that I can believe it to an extent.

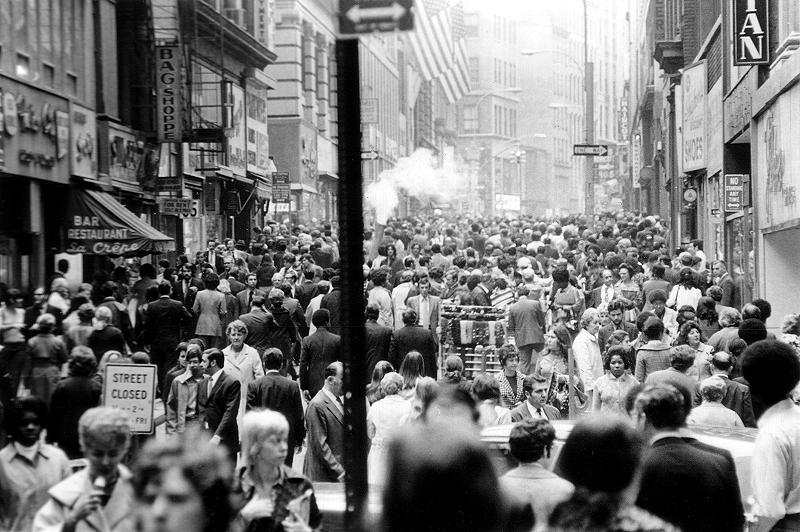

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own.

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own.

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own.

This startling claim gathers more credence when you think about the vast majority of the people in the world that are not seriously capable of thinking for themselves. The phrase of "following the herd", an aimless hive-mind, describes this phenomenon perfectly. Following what everyone else is doing is the norm for these individuals. On a small scale, these individuals might have their checkbook balanced and their schedules planned, but if you survey their global quality of life, especially in terms of ethics, these people lack the intellectual robustness to comprehend their life's meaning on their own. At this point, my conclusion is that Aristotle was definitely on to something when he defines the natural slave. Though I might not agree with every characteristic that he associates with them, I do accept that there are persons capable of understanding human reason, though incapable of vigorously applying it themselves.

But to return to the initial claim, Aristotle's view that slavery could ever be both "just and beneficial" is still very difficult to swallow, despite the natural slave only being fit for physical labor (as shown above). Though without any guidance to his labors, he would be useless and unproductive. For it to be just, it would have to be in accordance with the virtue of justice and fittingness; and for it to be beneficial, it would need to be in the individual's best interest to be ruled by another man.

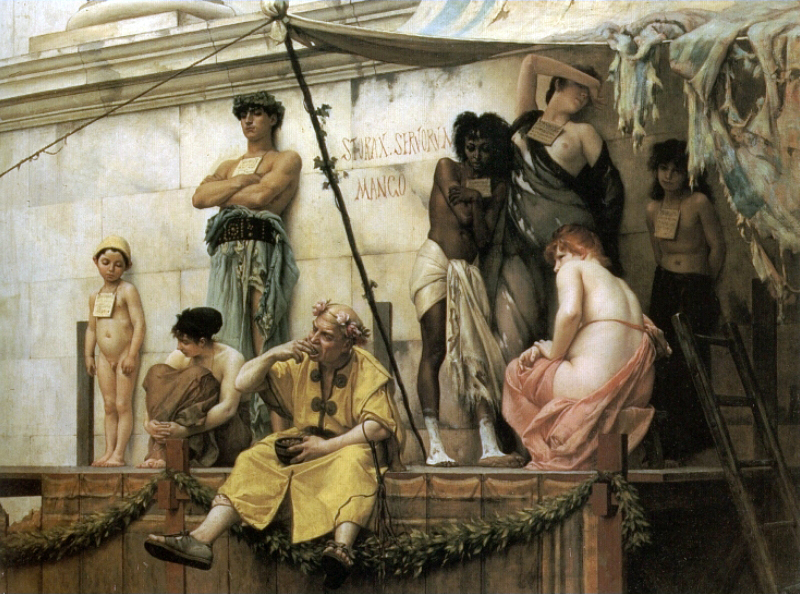

If a natural slave were to be ruled by another man, then who more beneficial to his interests than the virtuous, or eudaimon, man? Given the master's virtue, he would be of a superlative intellect, as contemplative wisdom, along with action-based practical wisdom, are the crowning achievement of the virtuous man and the most visible marks of his intellectual prowess.

Furthermore, without the capacity for agile rational activity, natural slaves are incapable of full human virtue, according to Aristotle; however, in the company of a virtuous master, the natural slave could share in his master's intellectual wisdom and share in living a virtuous life. Aristotle is very scrupulous when it comes to assigning the term, "virtuous". Both excellent acts and thoughts are require for the virtuous man, and on those grounds, the natural slave is disqualified from the title unfortunately. While I agree with this on the grounds that to achieve the highest status of any human being, you must perform your function the best, I believe there is a similar value and virtue associated with knowing your intellectual betters and modeling your conduct and contemplation after theirs.

And it is here that I think we have come across the most helpful and universally practical nugget in this lonely corner of Aristotle's political theory. Modern thinkers would never have discovered it because modern thinkers wouldn't have made it past the first paragraph. But we have. To some degree, we are all natural slaves; there is something deficient in our human understanding and it's something we can always work on. We need to make our understandings subservient to virtuous men; we must sit at the feet of the intellectual masters and allow ourselves to be guided by their practical and contemplative wisdom. In modern terms, it is comparable to discovering our role models and fashioning our thoughts and behavior from theirs.

To conclude, when considering Aristotle's political and ethical theory in its entirety, I believe he presents the most mature and responsible blueprint for a society that permits servitude. His biological (natural) perspective may overstep its bounds in some respects to a comprehensive understanding of the nature of all human beings, but in the end, he holds the masters of other men to high standards of conduct and responsibility in governing those under their charge. And in applying Aristotle's theory of natural slavery broadly with a little humility, we discover that we could all allow ourselves to cease our intellectual rebellions and naturally "enslave" our minds and hearts to men and women of high and admirable virtue.

If a natural slave were to be ruled by another man, then who more beneficial to his interests than the virtuous, or eudaimon, man? Given the master's virtue, he would be of a superlative intellect, as contemplative wisdom, along with action-based practical wisdom, are the crowning achievement of the virtuous man and the most visible marks of his intellectual prowess.

Furthermore, without the capacity for agile rational activity, natural slaves are incapable of full human virtue, according to Aristotle; however, in the company of a virtuous master, the natural slave could share in his master's intellectual wisdom and share in living a virtuous life. Aristotle is very scrupulous when it comes to assigning the term, "virtuous". Both excellent acts and thoughts are require for the virtuous man, and on those grounds, the natural slave is disqualified from the title unfortunately. While I agree with this on the grounds that to achieve the highest status of any human being, you must perform your function the best, I believe there is a similar value and virtue associated with knowing your intellectual betters and modeling your conduct and contemplation after theirs.

And it is here that I think we have come across the most helpful and universally practical nugget in this lonely corner of Aristotle's political theory. Modern thinkers would never have discovered it because modern thinkers wouldn't have made it past the first paragraph. But we have. To some degree, we are all natural slaves; there is something deficient in our human understanding and it's something we can always work on. We need to make our understandings subservient to virtuous men; we must sit at the feet of the intellectual masters and allow ourselves to be guided by their practical and contemplative wisdom. In modern terms, it is comparable to discovering our role models and fashioning our thoughts and behavior from theirs.

To conclude, when considering Aristotle's political and ethical theory in its entirety, I believe he presents the most mature and responsible blueprint for a society that permits servitude. His biological (natural) perspective may overstep its bounds in some respects to a comprehensive understanding of the nature of all human beings, but in the end, he holds the masters of other men to high standards of conduct and responsibility in governing those under their charge. And in applying Aristotle's theory of natural slavery broadly with a little humility, we discover that we could all allow ourselves to cease our intellectual rebellions and naturally "enslave" our minds and hearts to men and women of high and admirable virtue.

.jpg)