|

| Amphitheater at Epidauros |

This is a post from the series, "The Highest Human Science". Click here for a complete list of all posts in the series.

Although our previous post in ancient Greek philosophy in this series was of a bunch of guys with some pretty crazy ideas, at least they were using their brains. Unfortunately, Greece was plagued by a rampant intellectual disease known as sophistry.

Although our previous post in ancient Greek philosophy in this series was of a bunch of guys with some pretty crazy ideas, at least they were using their brains. Unfortunately, Greece was plagued by a rampant intellectual disease known as sophistry.

The Sophists, as they were called, were the primary communicants of this sickness of the rational soul. Many of them were accomplished individuals in various fields of study. However, their aim was not towards the discovering of truth; rather, it was because intellectual prowess brought benefits. Their "expertise" gave them power and influence over others. Their opinions were highly respected by the like-minded, and they were praised and held in high esteem. Ultimately, the sophists practiced their art for the recognition it won them and the pleasure that their intellectual vanity afforded them

One of the primary teachings of the sophists was relativism or, more specifically, moral relativism. The arguments for their teachings were mostly attempts to rationally pick apart the established order without making any honest attempt at putting something back in its place. Relativism, or the theory that all laws are arbitrarily set by man and that man is his own judge of what is true, was the latest in intellectual pessimism and indeterminism. This was their primary doctrine and would have destroyed intellectual progress if it were not for one man.

Socrates. Yes, though present culture has bestowed upon Albert Einstein the bizarre distinction of using his name as an intellectual insult (e.g. "way to go, Einstein"), Socrates, in my humble opinion, should be the runner-up. He taught for free to anyone who would listen and preferred to ask questions of others to illustrate his philosophy. That is to say, he did not put forth a specific "philosophy" for men the consider; rather, he required them to think about the topics of greatest importance.

One such encouragement was his focus on essence. Socrates taught that in our rational discussion and thought, we must always seek to separate accidental qualities (might also be referred to as secondary or unnecessary qualities of that being's nature) from those essential qualities (qualities that are primary and necessary to that being's nature). For example, a being is not a "human being" unless it has the capacity for rational thought. Or a being is not a "plant" if it does not have the ability to grow, nourish itself, and reproduce. These things are essential to the constitution of that being, because you would not call a being "human" unless it had the capacity to think, or a "plant" unless it had to capacity to grow. Furthermore, accidental qualities are things such as having blue eyes (which is not essential to constituting a human; if it were, all people with green eyes wouldn't be "human") or having a stem or stalk (many plants do not have these either).

Socrates also laid the ground-work for rational discussion, known as the Socratic method. The method counter-acted the flourishing wordplay of the Sophists and gave rational discussion the means to achieve its goal of truth. It aimed at creating a coherent structure of logic and reasoning that would explain reality for all to understand. This essentially set rules for rational discussions and served as an excellent guide for those wishing to understand the truth for themselves.

However, Socrates' biggest contribution to philosophy, by far, is that he redirected the Sophists' aimless intellectual wanderings and set rational thought upon its purpose: the truth. He sought to reform the human intellect, which had been poisoned and misled by sophistry. He did not teach men what to think by writing down specific doctrines; instead, he taught them how to think in the middle of a world where the novelty of an idea was more important than its agreement with the truth.

|

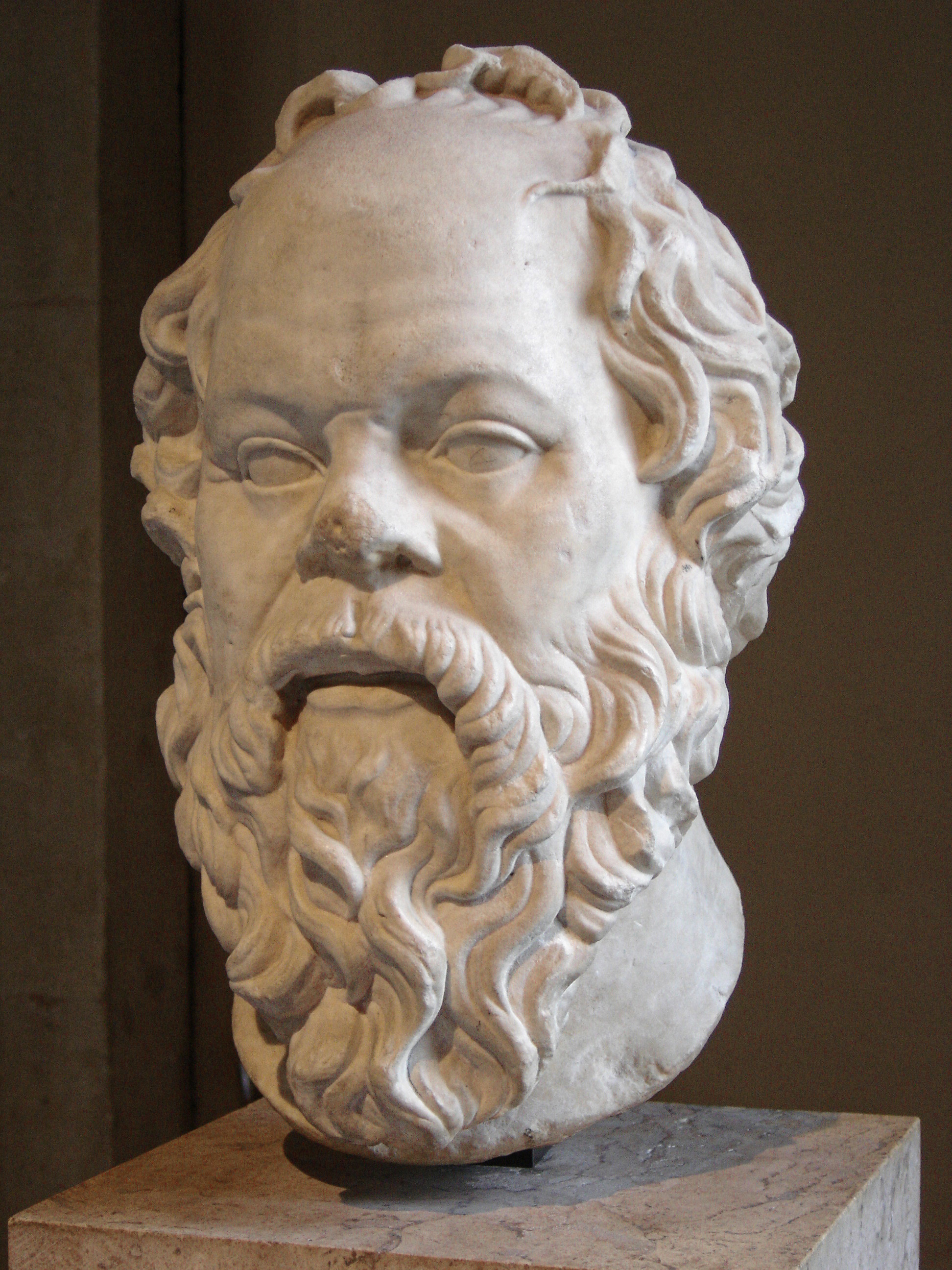

| A bust of Socrates by Lysippos |

One such encouragement was his focus on essence. Socrates taught that in our rational discussion and thought, we must always seek to separate accidental qualities (might also be referred to as secondary or unnecessary qualities of that being's nature) from those essential qualities (qualities that are primary and necessary to that being's nature). For example, a being is not a "human being" unless it has the capacity for rational thought. Or a being is not a "plant" if it does not have the ability to grow, nourish itself, and reproduce. These things are essential to the constitution of that being, because you would not call a being "human" unless it had the capacity to think, or a "plant" unless it had to capacity to grow. Furthermore, accidental qualities are things such as having blue eyes (which is not essential to constituting a human; if it were, all people with green eyes wouldn't be "human") or having a stem or stalk (many plants do not have these either).

|

| The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David |

However, Socrates' biggest contribution to philosophy, by far, is that he redirected the Sophists' aimless intellectual wanderings and set rational thought upon its purpose: the truth. He sought to reform the human intellect, which had been poisoned and misled by sophistry. He did not teach men what to think by writing down specific doctrines; instead, he taught them how to think in the middle of a world where the novelty of an idea was more important than its agreement with the truth.

.jpg)